Greece’s Papandreou May Have to Ditch Fiscal Pledges

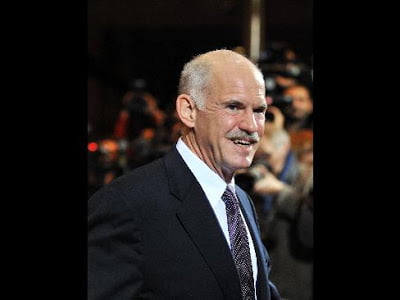

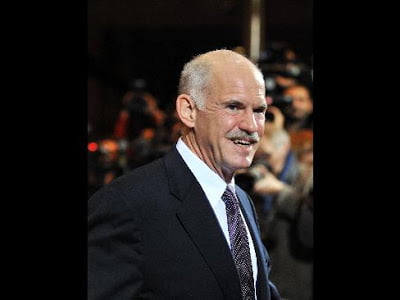

Dec. 7 (Bloomberg) — Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou may have to jettison the promises that won him October’s election if he’s to convince investors he can tackle the worst fiscal crisis in 15 years.

Within weeks of coming to power promising higher spending and more pay for civil servants, his government revised data to show Greece’s deficit will reach 12.7 percent of output this year, four times the European Union’s limit. Greek stocks and bonds were then roiled when the Dubai crisis made investors question whether the EU would stand behind Greece’s $450 billion in outstanding bonds.

“The Greek government has to create a platform with the people so that they are behind the new plans,” said Rob Dekker, who helps manage $145 billion in funds at F&C Asset Management Plc in Amsterdam. They must show the EU and investors “ they are serious about reducing the deficit. I don’t think they can spend their way out of the budget deficit, that’s not how it works. The deficit is too big.”

Papandreou’s government will present a new deficit plan to the EU in January as Greece tries to stave off possible sanctions for violating the deficit rules. Investors say he needs to reverse course and sell unions, voters and his own allies on the need to cut spending and boost revenue by about 10 percent of economic output to get the shortfall back within the limit.

Adding to the pressure, Standard and Poor’s Ratings Service today said Greece’s long-term sovereign credit rating may be cut from A-, while European Central Bank President Jean-Claude Trichet said the country must take “courageous” decisions to close the budget gap.

“The fiscal consolidation plans outlined by the new government are unlikely to secure a sustained reduction in fiscal deficits and the public debt burden,” S&P said in a statement.

Investors appear similarly skeptical. The difference, or spread, between the yield on Greek 10-year government bonds and German equivalents widened to 192 basis points today, up from 108 basis points in August. That compares with 163 basis points for the debt of Ireland, which the EU predicts will have the bloc’s second-biggest deficit this year at 12.5 percent of GDP.

Greece’s benchmark stock index has dropped 12 percent in a month, compared with a 3.3 percent gain in the Stoxx 600.

Greece’s widening deficit and constant revisions of its own statistical data prompted EU Monetary Affairs Commissioner Joaquin Almunia to say on Dec. 2, “the problems in Greece are problems of the euro area.”

Papandreou won the election, gaining a 10-seat majority in Greece’s 300-member parliament, on promises of a 3-billion euro ($4.5 billion) stimulus package, that included higher wages, a one-off “solidarity” benefit for poorer Greeks, and more spending on health and education.

Former Prime Minister Kostas Karamanlis, who called the vote halfway through his second term to seek a new mandate to tackle Greece’s economic woes, pledged wage and hiring freezes and possible tax increases. He lost by the widest margin in almost 30 years.

Unions have already flexed their muscle under the new administration. A threat by ADEDY, the union of civil servants, said Nov. 19 to call a strike forced the government to limit the number of civil servants it would exclude from a planned 1.5 percent wage increase.

The EU can fine Greece as much as 0.5 percent of gross domestic product every year until the shortfall is back in line. Whether the commission would implement sanctions that would only aggravate Greece’s deficit and could harm the credibility of the EU’s economic governance remains to be seen, economists said.

“They’re trying to get that message across with Greece,” said Ioannis Sokos, interest rate strategist at BNP Paribas SA. “Dealing with this problem of moral hazard is always tricky, since at the same time they want to highlight that there is no chance of a euro member state defaulting.”

The showdown will begin in January when Greece submits a new plan to the EU detailing how it will trim the shortfall to 9.1 percent next year.

“We are all determined to do the right thing,” Minister for Economy, Competitiveness and Shipping Louka Katseli said in a Dec. 4 interview. Still, “it will take three years” to bring the deficit down to the EU’s 3 percent limit.

About 75 percent of the deficit reduction plan comes from raising revenue rather than cutting spending, Deutsche Bank AG economists Mark Wall and Thomas Mayer estimate. Much of that will come from a crackdown on tax evasion, a chronic problem in Greece that a series of governments have pledged to combat.

“Its banking on the hope that everything will turn your way,” said Elwin de Groot, an economist at Rabobank Groep in Utrecht, the Netherlands. “There are no strong measures like we are seeing in Ireland.”

The Irish government will announce on Dec. 9 it’s cutting spending by 4 billion euros, or 10 percent of GDP even after public-sector pay cuts triggered the biggest strike in 30 years.

“The Commission may be dissatisfied with a revenue-based correction,” for Greece, Wall says. “Lack of action on permanent measures to reduce spending was the key reason for the commission’s conclusion that Greece has not taken sufficient action already.”

Moody’s Investors Service, which has Greece’s A1 credit rating under review for possible downgrade, said that concerns of a credit crisis are “overdone.” One reason is that the government’s financing needs will ease next year even as the deficit rises. Greece has 17 billion euros less of bonds coming due in 2010 than this year, cutting its financing needs to about 47 billion euros.

The biggest risk is that creditworthiness will deteriorate further without government action, rather than be called into question by external events.

“In the absence of significant economic and fiscal reforms, the interests of the government’s creditors and those of other stakeholders would likely come into conflict with increasing frequency,” Sarah Carlson, an analyst in Moody’s Sovereign Risk Group, said in a Dec. 2 report.

To contact the reporter on this story: Maria Petrakis in Athens at mpetrakis@bloomberg.net

bloomberg.com

Ακολουθήστε το

Ακολουθήστε το