Jaish-e-Mohammad: A terrorist group based in Pakistan

Introduction

Source : Reuters – Masood Azhar portrait

Jaish-e-Mohammad’s origins

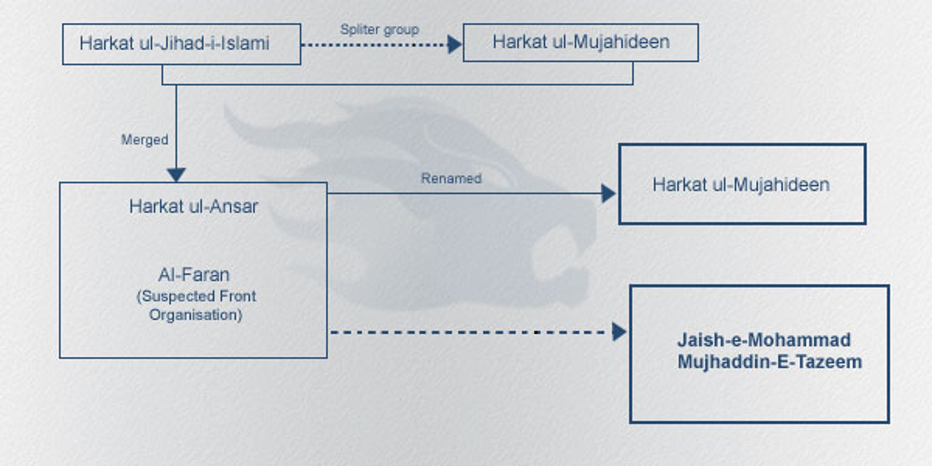

Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) also known as the Prophet’s Army is a Sunni Islamic extremist organisation, operating mainly in Indian-administered Jammu & Kashmir, whose aim is to overthrow Indian rule in Jammu & Kashmir and then to integrate the region into Pakistan under their own radical interpretation of Sharia law. The group was launched in March 2000 during a gathering at a stadium in Bahawalpur (Pakistan’s Punjab Province), the hometown of its founder, Maulana Masood Azhar, the son of a government schoolteacher who had graduated from an Islamic seminary in Karachi. In his early twenties, Masood Azhar dropped out of mainstream schooling to integrate a Pakistan-based terrorist organization, Harakat-ul-Mujahideen (HuM, formerly Harakat ul-Ansar, a Pakistani extremist group created to fight Soviet forces and support the jihad in Afghanistan). Quickly spotted for his oratorical skills, he became Secretary General of HuM in 1993 and travelled to various places, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Zambia and the United Kingdom, to give speeches, expand his network and raise funds for the organisation. Finally, Azhar was arrested in 1994 by Indian special forces while attempting to wage Jihad in Srinagar, in India-administered Jammu & Kashmir. Incarcerated for nearly 5 years in Indian jails, his release was achieved at a high price for India as he was exchanged with two other terrorists for the 155 hostages of Indian Airlines flight IC 814, hijacked on 31 December 1999 by HuM, with the logistical support of Al Qaeda (New York Times, 2020). On his return to Pakistan, instead of re-joining his former organisation, which had been forced to “reinvent itself” after been designated as a terrorist group by the United States, Azhar decided to form a new outfit. According to the Australian National Security Service, Azhar travelled to Afghanistan in 1999 to meet Osama bin Laden and obtain his “blessings”, and the support of the Taliban regime and Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), as well as the necessary funding for his venture. Supported by three heads of religious schools, Mufti Nizamuddin Shamzai of the Majlis-e-Tawan-e-Islami (MT), Maulana Mufti Rashid Ahmed of the Dar-ul Ifta-e-wal-Irshad and Maulana Sher Ali of the Sheikh-ul-Hadith Dar-ul Haqqania, almost three-quarters of the cadres of his former organisation joined Azhar (IPCS, 2005). The dawn of the new millennium marked the advent of Jaish-e-Mohammad.

Founder and current Amir (meaning leader) Masood Azhar is the face of Jaish-e-Mohammad, although the exact nature of the organisation’s command structure is unknown. Siddiqa, a former official who has interviewed several members of the Jaish, reported to the New York Times Magazine that the JeM is run almost exclusively by the Azhar family, making it a family business. Bearing witness to this fact is that from 2007 Masood Azhar became progressively more discreet, leaving the command to his brother Abdul Rauf Azhar, before reappearing in 2014. According to the South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP, n.d.), unconfirmed sources report a list of potential senior members of the organization:

- Maulana Masood Azhar – Amir

-

- Maulana Qari Mansoor Ahmed – Nazim Propaganda Wing (he is a resident of Bhurewala, Punjab)

-

- Maulana Abdul Jabbar – Nazim, Military Affairs (Former Nazim military affairs, (HuM)

-

- Maulana Sajjad Usman – incharge, Finance (Former HuM Nazim Finance)

-

- Shah Nawaz Khan alias Sajjid Jehadi & Gazi Baba – Chief Commander J&K (Former Supreme Commander HuM, J&K)

-

- Maulana Mufti Mohd. Asghar – Launching Commander (Former Launching Commander of HuM)

Source: South Asia Terrorism Portal

According to National Security Australia, the JeM has “several hundred members, including 300 to 400 active fighters” in Pakistan, in the Indian regions of South Kashmir and Doda, as well as in the Kashmir Valley. The supporters are mainly Pakistanis (minimal numbers of Kashmiris), but also Afghans and Arab veterans of the Afghan war against the Soviets. According to a special report by the Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies (2005), “A large number of men are recruited in the province of Punjab, nicknamed the ‘Jihad factory’, and more particularly in the districts of Multan, Bahawalpur and Rahim Yar Khan. Mainly because it manages to transcend a part of the population with the promise of a job and a better life, in a region where economic misery is widely present”.

Objectives and ideology

Jaish-e-Mohammad was originally founded with the aim of waging Jihad in Jammu & Kashmir to overthrow the Indian authorities and integrate Jammu & Kashmir into Pakistan under the aegis of Sharia law. By declaring a holy war against India, the stated aim was to free Muslims from the rule of the ‘ignorant’ (Indians) and to purge ‘infidels’ (Hindus, Christians, etc.) from the subcontinent. In its early days, the JeM therefore focused its terrorist attacks and terror campaigns on the Indian-administered region of Jammu & Kashmir and in India, in the hope that the Indian armed forces would withdraw. To this end, the JeM has publicly mentioned the existence of Madrassas (Muslims seminaries) across Pakistan, which train young men on the importance of waging Jihad against Indian rule. Religious education, which is central to the training of recruits, is also accompanied by training in fighting techniques, including suicide bombing. The JeM targets young boys to recruit them and turn them into ‘Fidayeen bombers’, literally meaning those who sacrifice themselves, to conduct suicide bombs attacks to ‘destroy’ those who ‘hurt’, such as the army, para-military forces, and the police. On 20 April 2000, the JeM carried out the first suicide attack in Jammu & Kashmir, when a Jihadist drove an explosives-laden vehicle against the gates of the Badami Bagh cantonment area in Srinagar, killing 5 Indian soldiers. This attack was the first of its kind in the history of terrorism in the Kashmir valley and created a modus operandi that has continued to this day, ravaging the region, and creating a climate of terror, with the new aim of causing maximum casualties, whether in the ranks of armed forces or civilians. These terrorist attacks testify both to the violence of this group and the technical and material resources at its disposal. The attack on the Indian Parliament on 13 December 2001, jointly orchestrated by the JeM and Lashkar-e-Taiba, leading to the death of 9 people, reveals the level of sophistication of which these groups are capable.

In addition, since its creation, the JeM has shared deep ideological ties with Al-Qaeda and the Taliban, calling for the destruction of India, Israel and the United States, and waging Jihad against governments that, according to their interpretation, ‘violate the rights of Muslims’. In 2010, Pakistan’s Interior Minister Rehman Malik stated that the JeM, along with Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan, were allied to the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. Mapping Militant Organizations, a Stanford University research project “documents the evolution of militant organizations and the links that have developed between them {the Taliban and the JeM} over time”. The JeM is said to have sent fighters to train alongside Taliban fighters at training camps in Afghanistan. With the fall of the Taliban regime in 2001, the organisation relocated its training camps to Balakot, in the North-West Frontier Province, Peshawar and parts of Pakistan-administered Jammu & Kashmir. However, this setback did not undermine the ties that bind the two organisations as in June 2008 the JeM’s operational focus shifted, and it decided to refocus its collective efforts on expelling foreign troops from Afghanistan shifting their focus from Jammu & Kashmir. Their complicity in the Afghan Taliban movement was evidenced by the late June 2008 public beheading by the JeM members of two Afghans in Pakistan, accused of passing information to international forces in Afghanistan (Australian government). During this period, the JeM was largely less active in Jammu & Kashmir, however, after the Taliban took Kabul in 2021, many JeM cadres were released and secured the Taliban’s full support in their venture against India before returning to Pakistan. On 27 October 2021, the Hindustan Times reported that the JeM Chief had met Taliban leaders, including Mullah Baradar, in Kandahar at the end of August 2021 to seek assistance in the fight against India.

Jaish-e-Mohammad’s most notable attacks

- Badami Bagh cantonment attack in Srinagar (20 April 2000): JeM carried out the first suicide attack in Jammu & Kashmir, when Afaq Ahmad Shah (19) a Fidayeen solider from Srinagar, ran an explosives-laden vehicle against the gates of the Badami Bagh cantonment, the army’s 15 Corps headquarters in Srinagar, injuring four army personnel and three civilians.

- Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly attack (1 October 2001): Three fidayeen suicide bombers, belonging to JeM, attacked the Jammu & Kashmir State Assembly building in Srinagar killing in the blast and ensuing firefight, 38 people civilians, office workers and policemen.

- Indian Parliament attacks in New Delhi (13 December 2001): The attack, carried out by 5 Jihadists affiliated to Let and JeM, took place 40 minutes after both houses of parliament – the Rajya Sabha and the Lok Sabha – had just been adjourned, while more than 700 MPs were still inside the parliamentary precinct. The terrorists drove into Indian Vice-President Krishan Kant’s car and opened fire on the Vice-President’s guards and security personnel. Among those killed in the hour-long shooting were two members of the Rajya Sabha parliamentary security service, 5 members of the Delhi Police, a female CRPF officer and a CPWD gardener.

- Assassination attempts of President Pervez Musharraf (December 2003): After President Pervez Musharraf officially supported United States in its war against terrorism, mainly toward Al Qaeda and the Taliban, the JeM launched two assassination attempts, which ultimately failed. The first assassination attempt, which took place in Karachi when the bridge over which the presidential car had just driven exploded, caused no casualties, but the second suicide attack killed 14 people.

- Indian Air Force’s Pathankot Airbase attack (2 January 2016): Claimed by the JeM and the United Jihad Council, the attack on the Pathankot air base, located near the Pakistani border, came in the wake of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Lahore, which was seen as an icebreaker to ease relations between the two countries. Four gunmen, disguised in Indian army uniforms, forced the defence of the airbase, and engaged in a firefight with the military until all the assailants were declared dead. This bloody attack, which resulted in the death of seven soldiers, followed another attack that took place in September at the Uri military base and claimed the lives of 18 Indian soldiers.

- Pulwama attack (14 February 2019): Adil Ahmad Dar (22), a JeM Fidayeen soldier from Pulwama district in Indian-administered Jammu & Kashmir, launched an explosives-laden vehicle against a convoy of 78 Central Reserve Police Force vehicles carrying members of the Indian paramilitary police on the Srinagar-Jammu highway, killing 40 Indian soldiers (Guardian, 2019).

State sponsorship: Pakistan & JeM

Pakistan is frequently pointed out by the international community of being a major sponsor of terrorism, with particular emphasis on the ambiguous relationship between Pakistani intelligence services and terrorist groups. In a report produced by the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution in 2008, Pakistan was described as “perhaps the most active sponsor of terrorist groups in the world”, while it also stated that “Pakistan, for example, has supported a range of groups fighting India in Kashmir, using money, weapons and training to influence their ideological agendas and targeting” (Byman, 2008). The Pulwama attack in February 2019, which killed 40 people, reopened the debate on the ideological and financial support provided by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence to the JeM, whose creation came at a time when the Pakistani army was justifying Jihad, aimed at ‘liberating’, in case of Jammu & Kashmir, annexing, territories, as a legitimate part of its foreign policy after this strategy proved effective in expelling Soviet troops from Afghanistan in 1989. Although the Pakistani authorities tend to deny this allegation, high-ranking personalities have made statements over the last decade contradicting the official version. Indeed, in an interview accorded to the Pakistani journalist Nadeem Malik in February 2019, Pervez Musharraf, former President of Pakistan between 2001 and 2008 and at the time in exile in Dubai, admitted that “Masood Azhar-led Jaish-e-Mohammed carried out attacks in India during his tenure on the instructions of the intelligence agency”. Asked about the lack of action taken under his tenure, he replied that “Those were different times. Our intelligence men were involved in a tit-for-tat between India and Pakistan…This was continuing at that time and amid all of this, no major action was taken against the Jaish. And I also did not insist {despite the assassination attempts}”. The last sentence reveals the lack of power of the civilian government over the military and the opacity that surrounds it as well as the depth of the relationship maintained between the ISI and JeM. Recently Imran Khan, former Pakistan’s Prime Minister between 2018 and 2022, acknowledged during a conference at the US Institute of Peace in Washington that the Pakistan Army had tolerated and even created terrorist groups in the past and that his country was still hosting between 30,000 and 40,000 terrorists. Such statements were again confirmed in an interview with the BBC in 2019 by Shah Mehmood Qureshi, Pakistan’s foreign minister under President Khan, who admitted that the ISI was indeed in contact with JeM leaders. According to him, the terrorist group had been contacted by the ISI and had denied any involvement in the Pulwama attack, thus contradicting their own claim of carrying out the attack which was published a few days earlier in various newspapers. The Foreign Minister also acknowledged the presence of Masood Azhar in Pakistan, saying that the Pakistani government was willing to initiate legal proceedings against him if the Indian government could provide “solid” and “inalienable” evidence of his involvement in the attack. This un-holy alliance between the Pakistani government and terrorist groups is described in detail in EFSAS’ Study Paper, ‘Pakistan Army and Terrorism; an unholy alliance’, published in 2017.

There are also more concrete signs to support this assumption, such as the Punjab governor’s complacency towards the JeM’s activities on his soil. In an article published in June 2010, the Economist quoted a political analyst in Lahore as saying that “not only is the Punjab government complacent, it has a somewhat ambivalent attitude towards extremists. It is fighting for religious votes” (The Economist, 3 June 2010). Residents report fundraising, pamphlet distribution and public gatherings to finance the Jihad campaign in Kashmir. The JeM also has a television channel and a newspaper “Zarb-i-Momin” written in Urdu and English in which their ideology is relayed. The group is also said to be politically aligned with the radical faction of Jamiat-Ulema-I Islam, a major Islamist political party led by Maulana Fazlur Rehman (ibid.; Mapping Militant Organizations 3 August 2012a). According to a special report by the Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies (2005), this association acts as an interface between JeM and Pakistani society, enabling them to obtain support and funding (IPCS, 2005). In addition, a report on violence in Pakistan published on 23 January 2014 by the International Crisis Group also mentions that the JeM has a base in Punjab and carries out its activities both inside and outside the country.

Jaish-e-Mohammad: a pawn in the Indo-Pak conflict

Jaish-e-Mohammad is one of several terrorist groups operating in Jammu & Kashmir, however it has unprecedented striking power. Indeed, the group’s attacks have more than once brought the two nuclear powers to the verge of a head-on war, earning it a singular position in the Indo-Pak conflict. For India, the terrorist group represents an existential threat to its internal security, and its dismantling is therefore at the heart of the country’s foreign policy. Pakistan, on the other hand, uses the JeM as a geostrategic asset to serve its own interests and achieve its reconquest objectives.

First wave of sanctions

The attack on the Indian parliament in December 2001 pushed the terrorist group into a new dimension, bringing it to the forefront of the international stage. This unprecedented attack led to sharp tensions between the two nuclear powers, which amassed their respective troops along the Line of Control (LoC) in Jammu & Kashmir and the International border between the two countries, gathering more than 800,000 soldiers on the border. Also known as the “2001-2002 India-Pakistan standoff”, it marked the largest military mobilisation between the two countries since 1971. Occurring in an international context of “war on terror” – launched by the United States after the September 11 attacks – this assault had put Pakistan and India, both officially committed to the United States, in the spotlight, forcing the international community to take major measure against the terrorists. Following the attack, the US State Department added the JeM to its list of foreign terrorist organisations, forcing Pakistan to take coercive measures against the JeM. The United Nations Security Council also reacted via the 1267 Sanctions Committee – formed in the aftermath of the Kenya and Tanzania bombings to implement sanctions on the Taliban and Al Qaida – by registering Jaish-e-Mohammed in 2001 on the Sanction List for “participating in the financing, planning, facilitating, preparing or perpetrating of acts or activities by, in conjunction with, under the name of, on behalf or in support of”, “supplying, selling or transferring arms and related materiel to” or “otherwise supporting acts or activities of” Al-Qaida Usama bin Laden and the Taliban (UNSC, 2023). Also known as the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh) and Al Qaida Sanctions list or as the UN global terrorists list, this list is a key instrument for States to use when enforcing and implementing the sanctions, namely assets freeze, travel ban, and arms embargo against individuals, groups, undertakings, and entities associated with or belonging to Al-Qaida, Usama Bin Laden and the Taliban (UN resolution 1267, 1999).

Internal reorganization to escape sanctions

Under international pressure, mainly from the US and India, Masood Azhar was arrested on 29 December 2001 for his alleged involvement in the attack but was released a year later after the Lahore High Court ruled that his arrest was illegal. It was only one year later, in January 2002, after a second failed assassination attempt against Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf and his “policy of purging terrorism”, that Pakistan finally decided to ban the JeM. Anticipating events, the JeM decided to pursue the same policy as its predecessor, 5 years earlier, and “reinvented” itself by renaming itself Tehrik-ul-Furqan. A JeM spokesman openly admitted that they had “withdrawn {our} money from bank accounts and reopened them in the name of {our} more low-profile supporters”. International regulators suspect that the Karachi-based Al-Rashid Trust, described as an educational and religious charity, holds the majority of the JeM’s funds. Since 22 September 2001, it is listed by the US State Department as one of 27 groups and organisations involved in financing and supporting a network of international Islamist terrorist groups. The JeM also took advantage of this reorganisation to invest in activities such as real estate, commodities trading and the manufacturing of consumer goods. The ease with which the money was transferred and used, demonstrates the gaping holes in Pakistan’s anti-terrorism laws. According to the UN Security Council, JeM members also set up two organisations registered in Pakistan as humanitarian aid agencies: Al-Akhtar Trust International (QDe.121) and Alkhair Trust, to supply arms and ammunition to its members under the guise of providing humanitarian aid to refugees and other needy groups. Although the JeM appears as a single entity on the international scene, the group has split into two, due to conflicts between its members, with Khuddam ul-Islam, headed by Masood Azhar, on the one hand, and Jamaat ul-Furqan, led by Abdul Jabbar, on the other. Arrested by the Pakistani authorities for his involvement in the attempted assassination of President Pervez Musharraf, Abdul Jabbar was imprisoned for two years, and released in 2004. Despite the Pakistani government’s ban on Khuddam ul-Islam and Jamaat ul-Furqan in 2003, members of both organisations still appear to be active in the country and enjoy full freedom of movement. However, the ban did not put an end to allegations that Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) continued supporting Jihadist militant groups such as the JeM.

UN designation as global terrorist

The lack of concrete action taken against the terrorist group has considerably heightened tensions between India and Pakistan, with the former now seeing Masood Azhar’s death as a security goal. Since 2009, following the Mumbai attacks in November 2008, India has been desperately trying to get Masood Azhar on the list of global terrorists of the UN, but each time it has faced a veto from China. The Chinese government, one of the five permanent members of the Security Council and a close ally of Pakistan, blocked Indian attempts three times, arguing that there was no evidence to show that Azhar was either alive or active (Lowy Institute, 2019). The Pulwama attack upset this balance, allowing India’s Ambassador to the United Nations, Syed Akbaruddin, to submit evidence to the sanctions committee of Masood Azhar’s responsibility in the attack. According to audio recordings gathered by Indian intelligence, the JeM leader declared a few days after the attack that “if India did not cede Kashmir, the flames of jihad would spread throughout the country”. Faced with these new revelations and as its position was becoming internationally untenable, China finally reviewed its position, and, on 1 May 2019, the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh) and Al Qaida Sanctions Committee – which is a subsidiary body of the UNSC – declared Masood Azhar as a globally designated terrorist and registered him on the 1267 Sanction List, thus forcing Pakistan to freeze his assets, prevent him from acquiring weapons and ban him from travelling (UN resolution 1267, 1999). However, the report does not mention the Pulwama attack, but only highlights its links with the Taliban and al-Qaeda, and since then Azhar has been reported missing by the Pakistani authorities. In 2021, in his online magazine Al Noor, Azhar congratulated the Taliban on their takeover of Afghanistan and described it as a major victory for regional Jihadist groups. According to the Pakistani government, Masood left Pakistan for Afghanistan at the beginning of 2022 and since then they have urged the Taliban to arrest him, however the Taliban has denied this information.

New chapter in the India-Pakistan conflict

After the Pulwama attack, the Indian army announced that it had carried out surgical strikes in the Balakot region, where the JeM’s headquarters were located (Reuters, 2019). Indian Foreign Minister Vijay Gokhale claimed at a press conference that the strikes had killed a “large number” of militants, including commanders, and that there had been no civilian casualties (BBC, 2019). However, this version was quickly denied by the Pakistani authorities, which announced that the bombs dropped by Indian fighters had only hit trees. Pakistani army spokesman Major General Asif Ghafoor insisted that the madrassa had done “no harm” and that Indian allegations that it was a terrorist training camp were “baseless” (BBC, 2019). These returns of the ball between the two sides were accompanied by several bombardments on each side of the LoC as well as air combat, in which an Indian plane was shot down. The Indian Air Force fighter pilot, Abhinandan Varthaman. H, whose plane was hit and crashed in Pakistan-administered J&K, was released a few days later by Pakistani forces as a sign of peace and appeasement. This incursion into Pakistani controlled territory, the first by Indian fighter jets since 1971, is part of a new military doctrine being applied by India (The Diplomat, 2023). Presented by Ajit Doval, India’s National Security Adviser under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, this new doctrine is based on the concept of “offensive defence”. In his own words, India’s aim is “to attack where the attack comes from”, in contrast to the hitherto prevailing doctrine of “defensive offence” (The Times of India, 2016). The architect of this policy, Ajit Doval, is none other than the man who, 24 years earlier, led the negotiations when HuM hijacked flight IC-814, leading to the release of Masood Azhar. This new way of reacting to the attacks marks a new turning point in the Indo-Pak conflict.

Conclusion

Considering the various challenges facing India and Pakistan, it is difficult to have a clear vision of the future of the region. What is certain, however, is that Jaish-e-Mohammad will undoubtedly play a crucial role in that future, both in easing tensions between the two countries, with the arrest of Masood Azhar for example, or in exacerbating them. With the advent of the Taliban in Afghanistan, the terrorist group could quickly find new support for its plans to export Jihad against India.

Over and above the ambiguous relationship between the Pakistani authorities and Jaish-e-Mohammad, it is the entire chain of operations that the country needs to review if it wants to avoid once again being placed on the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) “grey” list or worst on the “black” list. In 2018, the United Nations Security Council’s Sanction List included around 139 of individuals and entities from Pakistan out of a total of 345. Moreover, the stability of the country is also at stake, as Pakistan is increasingly prey to internal power struggles, seemingly caught up in its own demons. Indeed, terrorist groups are exploiting the current political and economic situation to expand their ranks and multiply their attacks, since the Taliban takeover, as in August 2021, Pakistan witnessed a mindboggling 51% increase in the number of terrorist attacks (PAKPIPS, 2022). Over a one-year period, from August 2021 to 2022, the country recorded more than 250 attacks resulting in the deaths of more than 433 people, representing a 47% increase in casualties as compared to the previous year (PAKPIPS, 2022). Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, a terrorist group based in Pakistan that seeks to overthrow the government by waging a terrorist campaign, claimed responsibility for most of these attacks, which mainly targeted Pakistani security forces and Chinese infrastructure (USIP, 2022). The main grouse of Pakistan, that the TTP is using Afghan territory to target Pakistani and Chinese targets in Pakistan comes across as misplaced and hypocritical if Pakistan’s colourful history in this very sphere is taken into consideration. While terrorism in any form cannot be condoned, no matter where it occurs, it is equally true that what groups such as the TTP are accused of doing to Pakistan today is exactly what Pakistan has done for several decades to both its western and eastern neighbours, Afghanistan and India, respectively. In Afghanistan, Pakistani spy agencies have recruited, nurtured, funded, armed and unleashed generation after generation of terrorist fighters, including the Taliban, ever since the days of the Soviet occupation in the 1980s. To the east, Pakistan’s equally pervasive strategy has been to set up a succession of deadly terrorist groups under different names, only to re-christen these groups, as in the case of JeM and LeT, every time they came under the international radar. As Sami Yousafzai, a veteran Afghan journalist and commentator who has tracked the Taliban since its emergence in the 1990s, aptly put it, “Pakistan is angry that the Taliban are copying its playbook by hosting a militant group hostile to a neighboring country”.

While the Pakistani State and the Pakistani people need to draw appropriate lessons from the impact that the repeated mobilization of terrorist and extremist assets by the establishment has had on their country’s polity, society, economy and security, with the intriguing revival of the extremist Difa-e-Pakistan Council in April 2023, the message for the FATF and other international anti-terrorist bodies is equally clear – the Pakistani terror machinery is openly back in action.

More than ever, the South Asian region is facing a growing terrorist threat, and the resurgence of terrorist groups such as the JeM is a signal not to be overlooked. Even if both Pakistan and India would be loath to actively pursue a path towards confrontation, all it may take for the present volatile situation to flare up is a gory incident at the border or a horrific terrorist attack. The crux of the problem is in Pakistan military establishment’s unending liaison with hardnosed extremists and terrorists, and which at times of international pressure, more than often prefers subterfuge over sincerity.

Unless this comes to an immediate end, peace and stability will not return to Pakistan’s frontiers, nor to the wider region of South Asia.

Ακολουθήστε το

Ακολουθήστε το