Debt disaster fears rumble from Athens to London

FRANKFURT (MarketWatch) — Rumors of a debt disaster are swirling around Europe, from Athens to Madrid and all the way to London.

Investors have rushed to sell Greek bonds since the newly elected government of George Papandreou made a startling revelation: the deficit will soar to over 12% of gross domestic product this year, well above previous official projections.

Greece’s predicament has escalated concerns about contagion in other European countries whose finances are in poor shape. Just this month, the ratings of Greece have been cut both by Fitch Ratings, and, late Wednesday, by Standard & Poor’s, and major agencies have warned Spain and Portugal of possible cuts.

The market reaction has been swift, and brutal. The euro has dropped below the key $1.50 level. Credit-default swaps on Greek government debt — essentially, bets that Greece will default — have ballooned.

……….

Irish and Spanish institutions also have seen extreme bouts of turbulence of late.

The most vulnerable countries like Greece and Spain indeed confront a mounting debt burden, which will likely lead to more ratings downgrades and more market sell-offs. The path to fiscal health will require painful, unpopular reforms.

But, most analysts agree that the European Union will, if necessary, bail out its members and never let a country’s fiscal situation deteriorate to the point of sovereign default. Those rescue expectations continue even as terms of euro entry explicitly forbids such moves. See story on the EMU fudge.

“If you think Greece is going to default, you should sell all the bonds of Spanish and Italian and Portuguese companies, because you think the euro will fall apart,” said Philip Gisdakis, credit strategist at UniCredit. “And that is something that I think is completely exaggerated.”

“There is a lot of misunderstanding in the market about the importance of Europe and the euro-zone on a political level,” he said. “Europe is a question of warranties. They are going to support countries like Greece and Ireland.”

The members of the European Union — which is both a political and an economic alliance — are closely interconnected and have too much to lose if one of them defaults.

That is especially true for those 16 countries which share the euro as their common currency. See story on playing the crisis.

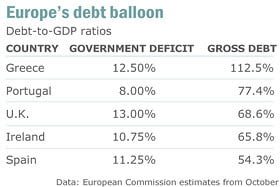

Greece’s debt troubles are hardly new; it has been running high public deficits for years, and the state of the economy is not making things any easier. Real growth will be nearly flat next year after falling into a recession in 2009. The economic slump, together with high budget deficits, is projected to push public debt from 112.5% of GDP this year to over 135% of GDP by 2011, according to European Commission estimates.

Projections of weak growth and rising borrowing costs make it very challenging for Greece to repair its finances. The closely watched yield spread between Greek and German government bonds has widened significantly. For ten-year bonds, for example, Greece has to pay 2.5 percentage points more interest than Germany.

“Consolidating public finances is truly a Herculean task,” said Christoph Weil, analyst at Commerzbank, in a note to clients. “The greatest savings potential is doubtlessly found on the spending side.”

In other words, Greece stands some chance of balancing its budget only if it implements massive spending cuts. Papandreou’s government has vowed to implement reforms, but such a route is riddled with political potholes, as the local population seems unwilling to accept tough measures. That again leads to the question of E.U. support.

“You have a budget deficit and that means you have to borrow, so debt keeps going up. Your growth has to carry you out of this debt spiral, but the economy is falling off a cliff,” said Jason Manolopoulos, managing partner of Dromeus Global Opportunities Fund, a fixed-income hedge fund based in Geneva.

“The European Union, at some point, will have to say here’s X [amount of money] to tide you over,” he said, commenting on Greece’s financial woes.

Marc Chandler, currency strategist at Brown Brothers Harriman in New York, believes that a near-term default or an exodus from the euro zone is unlikely.

“The most likely scenario seems to be some muddling through with measures that are not quite enough, but still a step in the right direction,” Chandler wrote in a note.

On the worry list

While Greece’s woes have been in the spotlight recently, several other countries are also getting some attention, including Spain, Ireland, and even the U.K. Analysts emphasize the importance of differentiating between European countries, because their predicaments are only partially comparable.

For example, Ireland’s deficit is high at 10.75% of GDP. However, its public debt ratio — 65.8% of GDP — in 2009 is roughly half of the debt ratio in Greece. Also, Ireland is planning massive spending cuts next year, while Greece has yet to implement the drastic structural reforms necessary to remedy the state of its public finances.

In Spain, the deficit is projected to rise to 11.25% of GDP this year from 4.1% in 2008. The collapse of the construction industry has triggered the worst recession in decades and sent the unemployment rate to the highest level in developed Europe.

The deficit of the U.K., which is outside of the euro-zone, will surge to over 13% of GDP this year from 6.9% previously, as a result of the sharp economic contraction and the loss of tax revenues from the financial sector and the housing market.

“If you extrapolate, then every country whose finances weaken will end up defaulting and the U.K. would be next,” said Adam Cordery, head of European and U.K. credit strategies at Schroders.

“However, that isn’t what tends to happen in a cyclical recession in relatively affluent societies that have a lot to lose, and Greece and Spain, like the U.K., would have a lot to lose,” he said in emailed comments.

A default scenario would require a persistently weak global economy and lack of action on the part of domestic authorities and the E.U., all events that are unlikely, according to Cordery.

“For sure, Greek and Spanish government bond yields could rise relative to Germany’s before they fall,” Cordery said. “But that doesn’t imply default – just a change in perceptions of the risks today.”

Polya Lesova is reporter for MarketWatch, based in Frankfurt.

marketwatch.com

Ακολουθήστε το

Ακολουθήστε το